Online Exhibition on the Prodigal Son in Visual Culture: Student Collaboration in Art, Media and Literature

This blog post focuses on an upcoming online exhibition on representations of the parable of the Prodigal Son in visual culture from the Middle Ages to the present day, curated by a group of five talented MA students.

Solitary Essay-Writing

Literature students spend much of their time writing essays. This is true both at the BA and MA levels: BA and MA degree courses work towards a thesis, in which students demonstrate their academic writing skills, as as well their research and analytical abilities. In the course of their studies, students prepare for this final ‘masterpiece’ by writing progressively longer and more complex research essays. My own background is in English literature – especially the ‘early modern’ era (i.e. the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries). The courses which I teach usually end with a research essay assignment, from short, 1200-word essays in year one of the BA in English to indepth, 5,500-word research papers at the MA level.

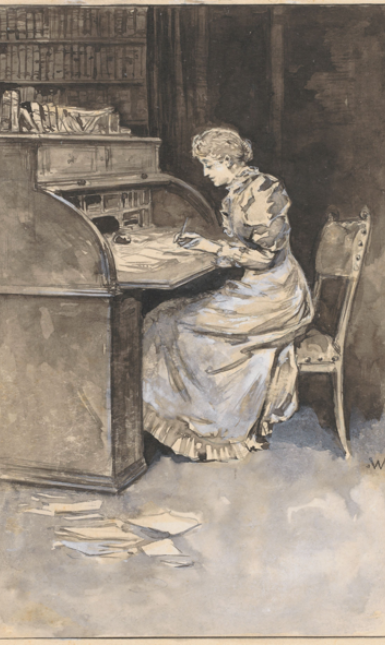

This form of academic training is crucial. Academic writing is a complex, deep skill which students can acquire only in an iterative learning process: they write an essay, receive feedback from their instructor, write another essay in which they process the feedback, receive feedback on this new essay – and so on. Yet writing (academic or otherwise) is often a solitary activity. Students therefore spend much of their time sitting alone at their desk – like the woman depicted in Willem Wenckebach’s drawing. And even when they do their writing in libraries or other communal spaces, their essay bears only their own name, and it is by and large the result of their own, individual labour.

Collaborative Learning

There is nothing wrong with working alone. Yet, as the covid-19 crisis has powerfully reminded us, it is ideally balanced by communal and collaborative activities. Not only does collaborative learning boost students’ well-being but collaboration skills are also important in their post-university professional careers. There is some irony in the fact that while students can be a bit wary of collaborative assignments during their studies, they often wish they had done more of them once they’ve entered the job market.

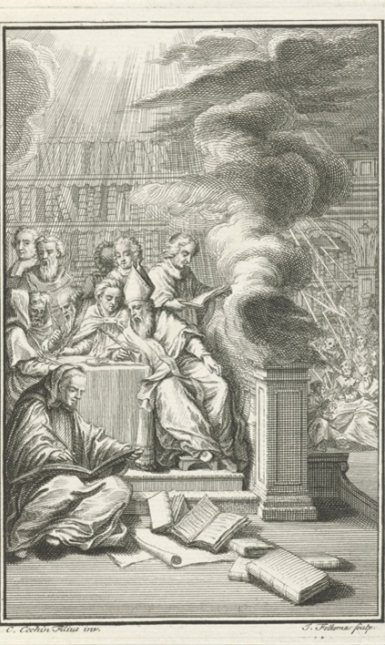

My project for the Leiden Teachers’ Academy examines how we can integrate collaborative forms of assessment more structurally into our literature teaching. How can we turn the academic analysis of literary texts into a collaborative enterprise, and enable students to become a bit more like the folks depicted in Jacob Folkema’s eighteenth-century etching Assembly of Clergyman: busily reading, writing and arguing together, illuminated by light from heaven? In fact, the seminar format to which we turn for most of our literature teaching revolves around group discussion, and it makes sense to extend this to our assessment methods. Of course, the question of what constitutes effective collaborative learning is a complex one, and I hope to reflect on this in more detail in future posts.

My interest in collaborative learning does not mean, of course, that I aim to replace essay-writing by other kinds of assigments, but rather that I seek to complement solitary academic writing with assignments in which students work together, for example on a jointly written journal article, on a blog post, or on an online exhibition – the subject of this blog post.

Entirely against my own expectations, the first substantial collaborative student project which I inititated as part of my LTA project focuses (mostly) on art history. So how does a project aimed at student collaboration in literary studies end up generating an exhibition on visual culture?

Online Exhibition: The Prodigal Son in Visual Culture

The answer to this question lies in a course which I taught for the first time last year, as part of the Research MA in Arts, Literature and Media offered at Leiden. The course is entitled ‘Imagining Reconciliation in Literature, Art and Media: Early Modernity to the Present Day’. In it, students examine representations of conflict resolution (or conflict management, to use a slightly less optimistic term) in literary texts and in visual culture (from seventeenth-century oil paintings to modern-day documentaries) from the seventeenth century to the present day. The course drew (and continues to draw) students specializing in literature, art history and electronic media.

One of the seminars in the course was devoted to a hugely influential paradigm for thinking about reconciliation: the Parable of the Prodigal Son, which Christ narrates to his disciples in Luke 15:11–32. This biblical parable has been the subject of numerous works of art, from the Middle Ages to the present day, while it’s also an important reference point in works of literature, from William Shakespeare’s play King Lear (1606) to Charles Dickens’ novel Dombey and Son (1846–1848) and the recent Gilead novels by the American writer Marilynne Robinson.

For this seminar, I asked students to find works of visual art which depict one or more moments in the parable. They found even more than I expected and we had a very fruitful and illuminating classroom discussion about the various strands, conventions and recurring topoi which recur in visual depictions of the Prodigal Son parable. The parable, it turned out, has served as a highly flexible basis for artistic expression, its various components downplayed or highlighted in different eras and in different artistic traditions.

One such narrative component is the prodigal son’s brother. In the parable, he disapproves of the warm welcome which his prodigal brother receives from the father. What to do with him in a visual representation of the parable? In many works of art, he is simply left out, simplifying in this way the emotional dynamics of the story: there is only a happy reunion between father and son, no disgruntled brother. Yet in some depictions – for example in a 1636 etching by Rembrandt – the brother stares back at the viewer, as if to challenge us, daring us to pass judgment on the prodigal son’s return.

I was so happy with the rich materials which the students gathered that I invited them to curate an online exhibition on representations of the Prodigal Son in visual culture from the Middle Ages to the present day. A group of five students volunteered, and got to work, combining their skills and expertise in literary studies and art history to produce a lively survey of the many different ways in which visual artists have imagined and reimagined one of the most canonical biblical parables. They selected the art works, wrote a concisive literary analysis of the parable itself, and a series of perceptive short close readings of each of the items in the exhibition. My own role was limited: the students worked together across disciplines (literature; art history; medieval studies; early modern studies; contemporary studies), dividing the tasks among themselves, and demonstrating what’s possible when students take charge – and then they look beyond their own ‘home discipline’.

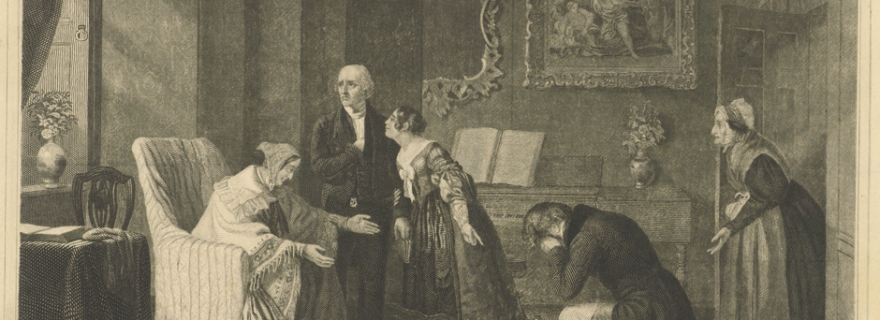

The exhibition will be hosted by Things that Talk, and is scheduled to go live this spring. By way of sneak preview, here is an 1845 steel engraving of the prodigal son’s return by Jan Frederik Christiaan Reckleben, in which the father is uniquely reluctant to forgive his prodigal son, and in which women play prominent roles (though the discontented brother is absent):